Do you know how Labor Day started and became a national holiday? It was started by labor unions in the late 1800s to celebrate the contributions and achievements of American workers. But in the late 1800s, conditions for American workers were deplorable – they had little to celebrate with long work weeks, poor sanitation, dangerous conditions, no job security, and low wages.

One woman made a profound impact on worker’s rights in the 1930s and 40s: Frances Perkins.

Frances Perkins was the first woman to become a Cabinet Secretary, appointed by FDR as Secretary of Labor. She wasted no time leaving an impact and a legacy that we feel today.

Fanny, as her family called her, grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts, and credits her grandmother, Cynthia Perkins, with imparting the wisdom that guided her throughout her life. From her grandmother, she heard stories about the French and Indian Wars, her family’s role in the colonists’ fight for independence, and she had a deep appreciation of her heritage “as well as a belief that the new nation, only a century old at her birth, held opportunities for all who sought and were willing to work for them,” according to The Frances Perkins Center.

While she was raised in a strict, Congregationalist, conservative Republican home, Fanny was always expected to attend college which was unusual for women at that time. She chose Mount Holyoke College, whose founder, Mary Lyon, advised her young women students to “Go where no one else will go, do what no one else will do.” A course that Fanny took in American economic history had a profound impact on her when she visited local mills and observed the conditions. She said later, “I was horrified at the work that many women and children had to do in factories. There were absolutely no effective laws that regulated the number of hours they were permitted to work. There were no provisions which guarded their health nor adequately looked after their compensation in case of injury. Those things seemed very wrong. I was young and was inspired with the idea of reforming, or at least doing what I could, to help change those abuses.”

After college, Frances moved to Chicago, and began working with the poor and unemployed at settlement houses. She later worked for an organization that diverted immigrant girls and black women from the South away from lives in prostitution, and with an organization that worked on alleviating childhood malnutrition in New York City.

She returned to her first passion for bettering working conditions when she began working for the NYC Consumers League on sanitary conditions, fire protection and legislation to limit working hours for women and children.

The next year, 1911, Frances was an eyewitness to the Triangle Shirt Factory fire, which killed 47 workers, mostly young women, who jumped from the 8th and 9th floors as fire raced through the building. After the tragedy, her appointment, at the suggestion of Theodore Roosevelt, to a Citizen’s Committee on Safety led to the passage of a comprehensive set of laws governing workplace health and safety, and set her on a career path to her most important work.

In 1928, the new governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, appointed Perkins to become the state’s Industrial Commissioner, with oversight over the labor department. In this position, she was not afraid to challenge the Hoover administration’s assertion in 1930 that employment was on the rise and the nation was recovering from the Depression, and the front-page coverage made her a national figure.

“Most of man’s problems upon this planet, in the long history of the race, have been met and solved either partially or as a whole by experiment based on common sense and carried out with courage.” Frances Perkins

With the election of President Roosevelt in 1932, her policies and positions in New York were about to move and be tested at the national level. When Roosevelt asked her to serve in his cabinet as Secretary of Labor, she gave him a set of policy priorities that he had to agree to before she would agree to serve: a 40-hour work week; a minimum wage; unemployment compensation; worker’s compensation; abolition of child labor; direct federal aid to the states for unemployment relief; Social Security; a revitalized federal employment service; and universal health insurance.

This was a blueprint for many of the protections and rights that workers enjoy today. By the time Roosevelt died and she had become the longest serving cabinet secretary, she had achieved every goal except universal healthcare.

Frances Perkins is probably not on the top of most lists of “women who have made a profound impact on American lives” – other names come to mind more readily. But she is a woman who was fearless in going where women did not go in her time. She was steadfast in sticking to her principles and standing up to the men in authority. She kept her eye on the prize – the betterment of conditions for American workers, and she was responsible for many of the workers’ rights that we have today.

“Out of our first century of national life we evolved the ethical principle that it was not right or just that an honest and industrious man should live and die in misery. He was entitled to some degree of sympathy and security. Our conscience declared against the honest workman’s becoming a pauper, but our eyes told us that he very often did.” Frances Perkins

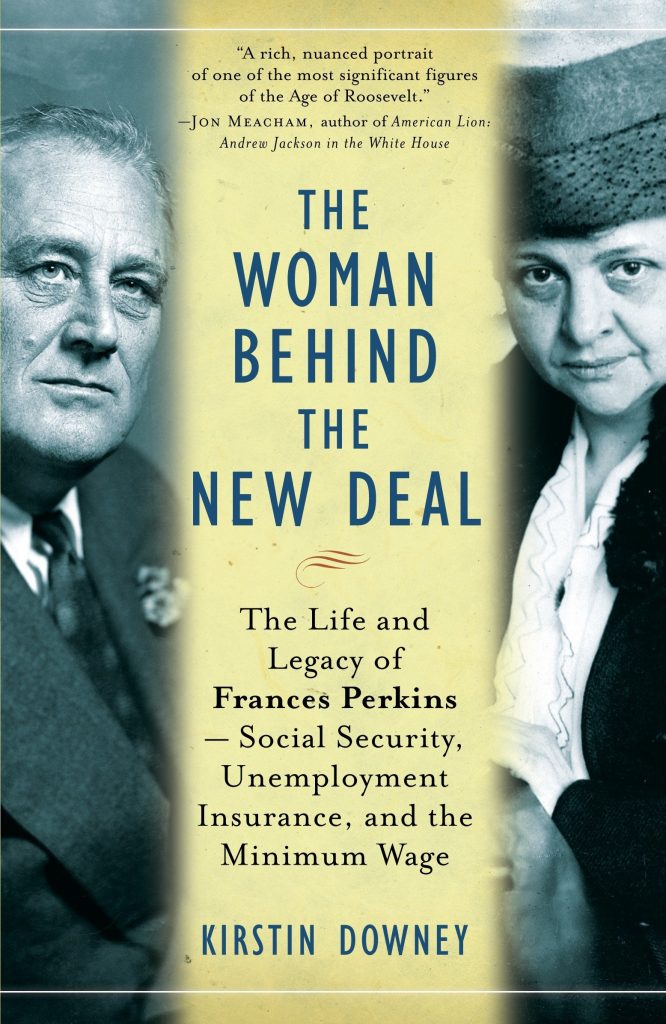

Want to learn more about her? Read The Roosevelt I Knew, her own biography of Franklin Roosevelt, published in 1946, or The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life and Legacy of Frances Perkins, FDR’S Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience by Kirstin Downey.

The featured image was originally posted to Flickr by Kheel Center, Cornell University Library at https://flickr.com/photos/38445726@N04/5279679474 (archive). It was reviewed on 16 May 2019 by FlickreviewR 2 and was confirmed to be licensed under the terms of the cc-by-2.0.